Nicholas Rimell, Lecturer in the School of Philosophy and Sociology at Jilin University, published Can the Future-Like-Ours Argument Survive Ontological Scrutiny? in the journal Medicine and Philosophy on October 6, 2021 (co-author: Matthew Adams).

The article takes the highly controversial issue of abortion in modern medicine as an entry for philosophical reflection: a popular argument against abortion is the “future-like-ours” argument; is this argument justified on metaphysical grounds? As the authors observe, a central assumption of the future-like-ours argument is that, even in the first trimester of a pregnancy ending in abortion, there is something that (absent the abortion) would have gone on to have conscious mental states. The authors argue that this assumption is true only if there is ontic vagueness. In this way, the authors argue, abortion ethics importantly depends on metaphysical issues, and in a way that the ethics of harming adult human beings may not.

Here is the link: https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jhab033

In the same month, Rimell's review of New York University philosophy professor Kit Fine's new book Vagueness: A Global Approach was published in the journal The Philosophical Quarterly, published by Oxford Academic.

Rimell observes that, while Fine devotes three chapters to explaining and account for vagueness, his approach is a fundamental departure from the traditional approach. The traditional approach has been to explain the concept of vagueness primarily in terms of local indeterminacy, i.e., borderline cases. For Fine, however, the notion of borderline cases is incoherent. Rather, vagueness should be explained as a global phenomenon that should include the indeterminate application of a predicate to a range of cases. Fine's demonstration also deviates from tradition in that Fine explains the indeterminacy characteristic of vagueness in wholly logical terms. Fine introduces the topic of vagueness and the three problems associated with it in Chapter 1. In the Chapter 2, Fine develops his own theory of vagueness, according to which a borderline case is impossible because it constitutes a violation of a single instance of the Law of Excluded Middle (LEM). In Chapter 3, Fine applies his theory to, among other things, the Soritical Problem. After presenting Fine’s account, Rimell argues that, while Fine's approach to vagueness is novel, the dismissal of borderline cases invites three serious challenges. Fine's robust response to these challenges is dubious for the reason that the content of his book is drawn from a lengthy manuscript that he is currently working on, as well as from recent publications of lengthy papers (p. xv). However, Fine's monograph has an important implication that offers a new, unified approach to several different philosophical problems. Moreover, Fine develops the above approach in a thoughtful and reader-friendly manner, and Fine's monograph will serve as valuable reading material for newcomers to vagueness and for experts on the topic alike.

Here is the link: https://academic.oup.com/pq/article/71/4/fiaa215/6055161

At the end of this year, Nicholas Rimell's book Representational Content and the Objects of Thought was published by Palgrave MacMillan, in association with Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press.

This book ties together a variety of important questions in metaphysics, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of language. It offers an exposition of leading versions of content internalism, including David Chalmers’s dual-content theory. It also offers serious challenges to the standard (and widely accepted) arguments against private propositions. To non-specialists, this book serves as a clear, careful introduction to central questions at the intersection of metaphysics, the philosophy of language, and the philosophy of mind: Are thought and meaning entirely in the head? What’s special about first-personal thought and speech? How (if at all) can we think about nonexistents, given that prima facie thinking involves a relation between a subject and an object of thought? To specialists, this book is designed to challenge the standard ways of thinking about these questions and to offer a unified response to them.

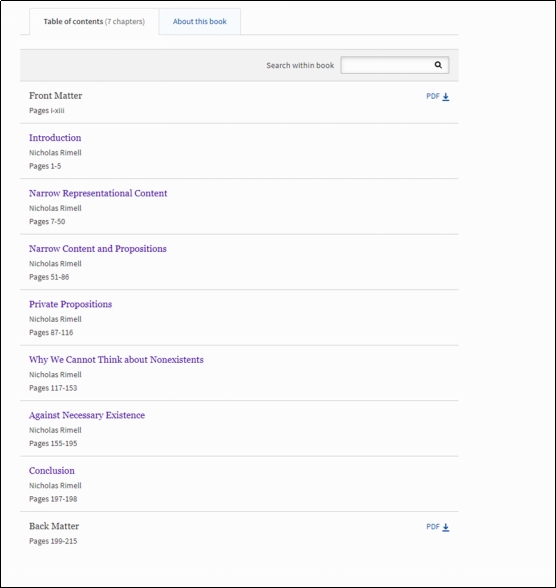

Divided into seven chapters, the introduction presents three difficult questions about mental representations. First, must thinking involve standing in a relation to an object of thought, and if so how (if at all) can we think about nonexistents? Second, do egocentric (i.e., first personal) beliefs have a special kind of egocentric representational content, i.e., do they represent the world as being a certain way that third personal beliefs cannot represent the world as being? Third, is the representational content of our thinking wholly determined by what’s ‘in the head’ and by how things seem to us from our perspectives, or is it in part determined (and not just caused) by our environments?

Chapter 2 is Narrow Representational Content. The goal of this chapter is to characterize the debate between externalists and internalists about representational mental content.

Chapter 3 is Narrow Content and Propositions. The traditional doctrine of belief goes back to Frege and consists of two theses. First, necessarily, beliefs are attitudes toward—and, consequently, inherit the contents of—propositions. Second, necessarily, propositions have truth values, and they have these truth values absolutely. Thus, there are no relativized propositions. It is commonly recognized that these two tenets jointly entail Content Fixes Truth (CFT), the claim that thoughts cannot have the same content while differing in truth value. Rimell argues that the traditional doctrine’s first tenet, all by itself, entails CFT and, accordingly, entails that externalism is true whereas internalism is false.

Chapter 4 is Private Propositions. Rimell argues that the first tenet of the traditional doctrine of belief has an additional consequence: our egocentric beliefs are attitudes toward private propositions. Rimell defends private propositions against traditional objections to them, and he then shows how his defense can be extended to serve as a defense of externalism.

Chapter 5 is Why We Cannot Think about Nonexistents. It has two aims. First, to defend the view that, given Content Fixes Truth (CFT), thought constitutively involves standing in a relation to what is thought about, from which it follows that we cannot think about nonexistents. Second, to present an error theory designed to explain what we are doing when we think we are thinking about nonexistent objects. In these cases, we are thinking about (non-coexemplified) properties.

Chapter 6 is Against Necessary Existence. The best alternative to the error theory presented in Chapter 5 focuses on necessitism, the claim that, necessarily, whatever exists exists necessarily. Rimell argues, among other things, that the reasons for the failure of necessitism argument are irrelevant to the arguments in Chapter 5. For causation to make sense, we must reject necessitism.

In the conclusion, Rimell discusses how the main claims defended in this book hang together. The first tenet of the traditional doctrine of belief says that, necessarily, if two thoughts share representational content (of some sort), then they are attitudes toward—and, consequently, inherit the representational content of—the same proposition. Rimell has argued from this ontological claim to an account of mental representation according to which: representational mental content is wide; egocentric beliefs are attitudes toward private propositions; and thought constitutively involves our standing in relations to the objects of thought, from which it follows that we cannot think about nonexistents.

Here is the link: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-16-3517-5